The Gjellestad Project is now well into the post-excavation phase. While there have been relatively few updates on the status of the project, this does not mean that the project has been at a standstill! A major component of the post-excavation work is the review of the field documentation –including curating photo lists, digitising field drawings, cataloguing finds, sampling, and analyses. Of course, in addition to these, there is also the conservation work.

Many people are probably wondering about what has happened to the preserved wood from the keel and frame. The wood from Gjellestad is now soaking in a water bath with PEG (polyethylene glycol) – a water-soluble wax that is used to impregnate archaeological wood found in wet conditions. The wax will gradually replace the water in the wood cells and when the PEG content has become high enough, the wood can be dried without the wood structure becoming further compromised. Effectively, the wax supports the cells during the drying process and works as scaffolding to keep them rigid afterwards – thus the wood will retain its original shape even after all the water has been removed.

Metallic finds, such as the iron rivets (of which there are over 1300), are in a unique position in that they must be treated individually. There are also over 8000 other fragments and objects that we will attempt to reassemble like a large puzzle to gain a more in-depth picture of the Gjellestad burial.

Rivet sample blocks

During the excavation, the archaeologists observed that the rivets from the Gjellestad ship were very fragile, prone to damage from the slightest touch, and could easily be pushed out of their original position by normal excavation practices.

The degree of fragmentation meant that the best strategy would be to lift the rivets out of the ship with their surrounding soil as soil blocks, also known as preparation samples. Using X-ray and CT technology, we can then peer into the blocks without interfering with them. As there were many rivets to extract, the project conservator constructed a special instrument that could extract the rivet and its surrounding material as a small soil block, measuring 8 x 12 cm. Once removed from the ground, these sample blocks were packaged tightly to keep air from getting inside and to keep their contents from moving about. The samples have been stored in cold rooms inside the museum and are removed only when they are ready to be systematically X-rayed, CT-scanned, and then preserved. This ensures that we get very good documentation of each individual rivet, and we can, in fact, see specific characteristics such as the length, shape variation, and positional orientation for each rivet. Additionally, the CT-scans allow us to document any mineralised wood that remains affixed to the rivets and any fragments of the planks (strakes) from the ship contained in the soil block.

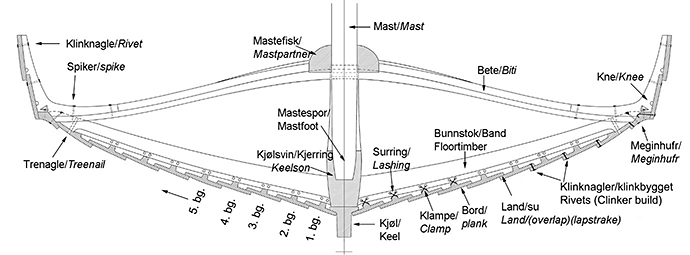

The CT scans will also be paired together with the total station measurements and photogrammetry models so that we can assemble the best possible collection of data for the reconstruction of the Gjellestad ship. As most of the wood from the interior of the ship had decomposed before our field work, the rivets represent the most important finds for the reconstruction. Not only are they important for understanding the positions of the planks, they will also inform us about the other parts of the ship construction. For example, any especially long rivets or rivets located at angles other than what we would expect from “regular” plank rivets, could indicate rivets that are fixed to the crossbeams (biti), floor timber, knees, or other wooden constructions found on the inside of the hull. The interior wood construction in a clinker-built boat or ship comprises the various internal elements of the ship that also reinforce the construction.

To date, we have scanned over 275 rivet sample blocks and while we have not had the chance to interpret all these scans yet, we have found a total of 12 new rivets after the excavation phase. This feature made by NRK 17 October describes the scanning and documentation work (only available in Norwegian).

Since the rivets are incredibly fragile, they need to remain in the soil that they were found in to keep them stable until they have been documented with CT-scanning. After the CT-scans are completed for each sample block, they are cleared to be preserved. This involves impregnating the entire block of soil with the silicate product TEOS (tetraethyl orthosilicate). TEOS was selected because it does not affect the colour of the material when it cures, and after curing the structure of the material is stabilised and strengthened—thereby preventing further deterioration. As such, TEOS safeguards that the contents of the sample blocks can be handled safely in the future – ensuring the opportunity to study both the rivets and the remnants of the planks contained inside.

The preservation of both the remaining ship footprint and the ship components has been a stated goal since the start of the project to ensure the possibility of a future on-site visitor centre. If the footprint of the ship is preserved, and a visitor centre constructed, it may be possible to return the sample blocks containing rivets to their respective “holes” in the ship. It has also proved possible to excavate the rivets from the sample blocks after they have been impregnated with TEOS. This provides both opportunities for dissemination related to exhibitions and, not least, for future research on the material.

Future visitor centre?

The possibility for a visitor centre at Gjellestad remains unclear. However, there is a strong desire both from Halden Municipality and the Viken County Municipality to create a centre where the footprint in itself will be an essential part of the story, and also an important component within a broader presentation about Gjellestad as a place within the surrounding region. Currently there are no funds to achieve this goal, but a group led by Halden Municipality is working on the case.

As we are still in the post-excavation phase, there is a limit to what can be seen at Gjellestad today. In addition to the beautiful Jell Mound, the location of the ship burial is visible as a low ship-shaped mound. The excavation of the Gjellestad ship was completed on 1 October 2021. After the closing of the excavation, the grave, with the remaining ship footprint, was covered with perforated plastic, fibre cloth, and then backfilled with sand. On the surface, a mound has been created that both visualises the location of the ship for the public, and at the same time serves as protection for the remains of the heritage monument. Grass and meadow flowers were sown on the new mound in the spring of 2022. However, this solution is not permanent, and one of the main reasons it was done this way, was to retain the possibility of creating visitor centre on the site. During the waiting period, archaeologists from Viken County Municipality will create new signs with QR coding that will direct visitors to online information webpages.

It is important to ensure good knowledge of the ground conditions around the footprint of the ship to assess how it can be incorporated into a building. Therefore, the first step in the investigation will be to carry out core drilling throughout the area.

Students sieving topsoil

Although the ship excavation has been completed, there has nevertheless been some activity at Gjellestad throughout the past year. During the excavation period 2020-2021 it was not possible to sieve through all the topsoil that lay above the ship grave, and some piles were left on site for later investigations. Students from the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History (IAKH) at the University of Oslo have helped the project by sieving the remaining soil on several occasions in 2022. The topsoil includes the remains of ship rivets and other finds from the locality that have been disturbed by ploughing. The students’ efforts help us to get an even better overview of finds from the topsoil layer over the ship, as well as an indication of how far objects in the plough soil layer have been moved because of agricultural activity. Thank you so much to everyone who has contributed!

Viking Nativity

At the same time as the post-excavation work on the ship grave progresses, new georadar surveys and coordinated metal detector searches are also being carried out on the fields around the ship. This is done under the auspices of the Viking Nativity research project, which you can read more about at Viking Nativity: Gjellestad Across Borders – The Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (niku.no).